The University of Michigan is among the leaders of a multinational partnership charged with determining the future success of the Great Lakes region.

The Great Lakes Futures project is an inaugural effort that makes use of 18 universities and the time of 29 master’s and doctorate students to develop policy recommendations for the next 50 years, and to better guide the application of federal grants to restoration projects.

It’s also serving as a training ground for the next generation of Great Lakes experts, connecting young students with the field’s research leaders.

The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Mackinaw breaks ice in Lake Superior this 2007 photo. The University of Michigan is collaborating with research institutions in the U.S. and Canada to form policy recommendations to protect the future of the Great Lakes.

AP File Photo

Marking the midpoint of the project’s yearlong process, 75 post-graduate students, researchers, advocates and policymakers convened Wednesday at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor to generate a consensus on the biggest future challenges facing the Great Lakes.

U-M is a participant in the Transborder Research University Network for Water Stewardship, which initiated the project.

For U-M, the effort is a part of its greater commitment to research and study of the Great Lakes. The university invested $4.5 million of its money, matching a $4.5 million, three-year grant from the Erb Family Foundation, to create the U-M Water Center in October.

How the project works

U-M is one of four research institutions coordinating the project, the other three being SUNY-Buffalo, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario and Western University in London, Ontario.

Twenty-nine graduate students, including two from U-M, were chosen from a field of applicants to participate. During the past five months, the students collaborated with their research partners in other states and across the northern border to project a range of outcomes that could face the Great Lakes in the future.

Don Scavia

Courtesy U-M

The students are analyzing the region's economy, geopolitics and governance, demographics and societal values, energy resources, aquatic invasive species, water quality, biological and chemical contaminants, as well as the effects of climate change on the lakes.

Don Scavia, director of U-M’s Graham Environmental Sustainability Institute, said U-M broadly solicited to its colleagues to contribute funding to the process, and only some were able to financially contribute to the project.

“That didn’t influence the student selection,” Scavia said.

Eighteen research universities — including U-M — as well as three research organizations each contributed between $10,000 and $20,000, giving the Great Lakes Futures project about $200,000.

Collected funds go towards paying for the time of the post-graduate students that did the work, Scavia said.

Part of the uniqueness of the project is the interaction and feedback the students get on their work from regional research bodies and representatives of governmental organizations, as occurred Wednesday at the workshop U-M hosted in Ann Arbor.

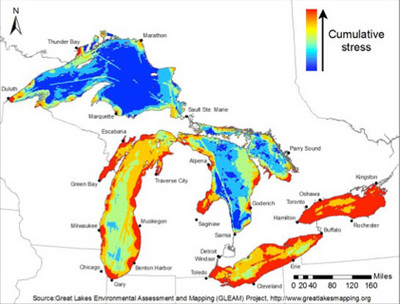

This graphic compiled by U-M researchers, published in December in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the comprehensive map to date of stressors in the Great Lakes.

Courtesy U-M

The interaction between the students, members of interest groups and representatives from policy bodies is extremely “uncommon,” Scavia said.

Students traveled to Ann Arbor for the conference on their own dime to contribute to the project, which they’ve been working on remotely with students from other universities — some of which are in other countries — on top of their regular coursework and thesis projects.

Lana Pollack, chairwoman of the U.S. section of the International Joint Commission, was among those that gave the students involved in the project feedback Wednesday at the forum.

The IJC assists the U.S. and Canadian governments in finding solutions to issues in waterways that touch both countries.

Pollack said she was impressed by the quality of the students’ work.

“It’s an impressive group of students and gives me hope for the future,” Pollack said.

For Pollack, the jury is still out as to how the Great Lakes Futures project will impact policy decisions.

“I think this is an invaluable component, but it’s only one component. It does try and get people to look forward; it’s easier to keep our focus on what we have today rather on where we’re going and how we get there,” Pollack said.

Also present at the Wednesday forum was Cameron Davis, senior adviser to Lisa Jackson, administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“What I really like is the long-term thinking,” Davis said.

It’s too early to tell how the project’s findings will impact policy decisions at the national level, Davis said.

The project is planned to submit final policy recommendations to groups including the Canadian and U.S. governments, states, provinces, Native American groups, Great Lakes cities, industry organizations, businesses and to the IJC in September.

Motivations

A major driving factor to the Great Lakes Futures project are the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) grants that have poured $1 billion into projects in Great Lakes states in the past three years — the single largest restoration program to date.

The GLRI program was an early product of President Barack Obama’s administration that was developed in 2009 and had its first round of funding — $475 million — available to municipalities in 2010. Since then, the amount of available grant dollars has decreased to $300 million for both 2011 and 2012.

The funding amount for the grant program in 2013 is still uncertain, and the first phase ends in 2014.

U-M’s Scavia hopes the Futures project can shape the way the second phase of GLRI grants are administered.

GLRI dollars have funded many Michigan projects, including a number of research projects at the University of Michigan.

Much of the allocation of GLRI dollars in the first phase has been to “fix past sins,” Scavia said.

With the second phase of GLRI funding, Scavia said he hopes the kinds of projects funded can be more forward-thinking, larger-scale, more proactive projects that will help the Great Lakes — which is where Scavia said the project’s policy recommendations will come into play.

U-M's Water Center

The Great Lakes Futures project is a way for U-M to kick off its renewed interest in Great Lakes research, U-M's Scavia says.

“With our new Water Center and our new focus on the Great Lakes, we wanted to really use this as a jumping off for us,” Scavia said of the project. "This is important to the University of Michigan: the Great Lakes region is really important and we want to contribute to the future.”

The project is an example of the kinds of things U-M’s new Water Center will be able to accomplish in the future, said Jen Read, deputy director for the center.

Jen Read

Courtesy U-M

Currently, the Water Center has a director, deputy director, three senior scientists and several part-time staff members. The program is seeking eight post-doctorate fellows, some of which specifically will be dedicated to the Water Center.

The Water Center is an opportunity to bring in younger researchers to the campus and to the field of Great Lakes research, Read said.

U-M formerly had many Great Lakes researchers on its Ann Arbor campus, but eventually those researchers moved on to other pursuits, Read said.

Read said the future of the Great Lakes region depends on the quality of the scientists being trained now, especially when it comes to staying competitive with other regions like Puget Sound, the Chesapeake Bay and the Everglades.

Amy Biolchini covers Washtenaw County, health and environmental issues for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at (734) 623-2552, amybiolchini@annarbor.com or on Twitter.