On the surface, it appeared nature was doing its best to reclaim the 16 acres along the Huron River off Broadway Street,l known in Ann Arbor as the MichCon site.

Underground, the soil tells a different, dirtier tale. There, years of burning coal and oil to make gas left behind a tomb of old industrial structures and soils contaminated with waste residues.

DTE Energy began a $3 million major environmental remediation project on the property this month, with the crux of the effort — soil removal — slated to start Sept. 10.

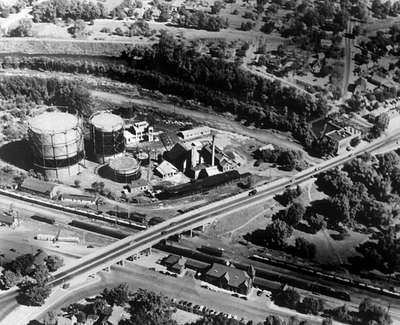

An industry's footprint

About 25,000 cubic yards of sediment contaminated with the byproducts of a long-lost industry will be scraped from about 1,000 feet of riverbank and the riverbed.

The former site of a manufactured gas plant that had its heyday in the first half of the 20th century, the MichCon property still has underground storage tanks that were used to hold the gas after it was created.

Close to the railroad, the gas plant was in the midst of the industrial district in Ann Arbor, near mills and coal yards.

Years of burning coal and petroleum to make gas left behind waste residues like coal tar and other impurities on the property — much of which was bulldozed to the edge of the site and fell into the river, said Shayne Wiesemann, senior engineer for DTE.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, there are more than 1,500 former manufactured gas plants across the country. Residues from processes at the plants may contain Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, petroleum hydrocarbons, benzene, cyanide, metals and phenols.

The Washtenaw Gas Company, formerly the Ann Arbor Gas Company, at Broadway Street and the Huron River in Ann Arbor that was purchased by MichCon in 1938.

Courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library / Ann Arbor Public Library

MichCon purchased the plant, built in 1900, from the Washtenaw Gas Company in 1938. The plant manufactured gas full time until natural gas became available to Ann Arbor in 1939. After that, the company used the plant to produce gas at peak demand times until the late 1950s. The most recent addition to the property was a service building in the 1960s, but it was torn down after being closed in 2009.

When DTE acquired MichCon in 2001, it inherited the company’s polluted sites — of which there are about 15 across Michigan. The company has since worked with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to clean them up.

The goal of the remediation project is to remove the soil that people are most likely to come in contact with along the riverbank and in the riverbed

This is not the first time environmental remediation projects have been conducted at the site. In 1998, 1,680 cubic yards of soil were excavated from the western part of the property. That was followed by installation and operation of a groundwater treatment system from 2000 to 2005.

Another 4,340 cubic yards of soil were removed from the eastern part of the property in 2006, followed by removal of a storm sewer outfall in 2011.

The projects have lent themselves to years of data and investigative tests, in addition to soil sampling and testing which was done in advance of the latest project, Wiesemann said.

Monitor wells installed for a previous project did not reveal residual contamination from the manufactured gas process in the groundwater, Wiesemann said. However, tests have shown ammonia in groundwater exceeding safe levels in several locations, he said. The source of the ammonia is not clear.

Tests have indicated a presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in river soils north of the site, with the highest concentration immediately adjacent to the site.

Soil and water tests conducted south of the MichCon site have not indicated the contamination has migrated downriver, Wiesemann said. Tests of the river water also have not indicated it is contaminated, he said.

Digging up pollution

Trees and undergrowth were the first to be removed from the site to give crews access to the soil underneath. Three landmark trees were saved — including the oldest tree on the site, a 51-inch cottonwood.

Hidden beneath an asphalt parking lot that takes up about one-fourth of the property lies a “hot spot” of contamination: five or six of the underground storage tanks and structures that will be excavated as a part of the project.

The amount of soil that will be removed from a 1,000-foot-stretch along the Huron River varies according to location on the property and was determined by tests.

DTE hired Terra Contracting of Kalamazoo for the job. Terra is the same company that cleaned up the Kalamazoo River following the Enbridge pipeline spill.

The most polluted area is in the riverbed and on the riverbank directly across from where the Argo Cascades empty into the main Huron River. The top 2 to 5 feet of soil will be removed from a swath of riverbank and riverbed.

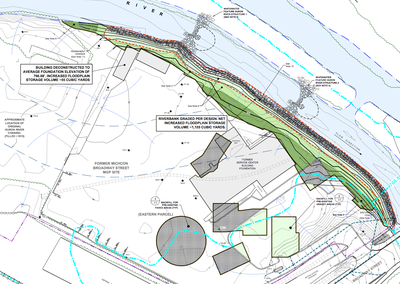

Soils from the green shaded portion and the circles indicating underground storage tanks on this site map will be removed in the current remediation project by DTE Energy.

To contain the contaminated sediment as it is dredged from the riverbed, special booms and barriers will be placed in 400-foot-long segments surrounding the activity. The barriers will be moved three times during the project, Wiesemann said.

DTE Energy will be working with the city’s Parks and Recreation Department to ensure that dredging is done when few canoeists, kayakers and tubers are on the Huron River en route from the Argo Dam to points downstream.

As the contaminated soil is scraped and dredged out, air quality will be monitored for particulate matter, volatile organic compounds and methane as a safety precaution, Wiesemann said.

Because of the nature of the waste that is being removed, people in the area may smell something similar to creosote — or if you go by Wiesemann’s nose, mothballs.

“The odor is not indicative of a health risk,” Wiesemann said.

Dirt contaminated with by-products from the manufactured gas process is not deemed as hazardous waste, Wiesemann said. The dirt from the MichCon site will be transported to the Veolia Arbor Hills Type 2 Sanitary Landfill in Northville, where it likely will be dumped over the household trash as daily cover, Wiesemann said.

Because the contaminated soil does not pose an immediate risk to human health, workers will not have to wear hazardous materials suits while working at the site. The site is considered contaminated based on long-term exposure limits for the slew of chemicals that could be in the residual waste buried on-site, Wiesemann said.

Going forward

Not all of the contaminated soils will be removed in the project, Wiesemann said. Much of the eastern half of the property in the “upland” portion of the site is covered in asphalt, and will remain that way until DTE knows what the plans are for the property.

Clean soil will be trucked in to backfill the areas that were excavated as a part of the project.

The riverbank will be graded at a more gradual slope. After the impacted soil on the shoreline is removed a cap made of composite particles and low-permeability clay will be installed as a precaution to make sure contaminants from the upland portion of the sight do not migrate to the river.

On top of the cap, about 30 inches of glacial stone and sediment will be installed to provide for erosion protection and for plant habitat.

Though Wiesemann said tests have not indicated a presence of residual contamination in the groundwater on the site, the cap serves as a precautionary measure in case there is migration of contamination in the future. Most of the contaminating materials aren’t soluble in water and would float on the surface, Wiesemann said.

Location of the MichCon site in Ann Arbor.

Courtesy of city of Ann Arbor

DTE intends to remediate the site to residential-level standards. The utility is only required to clean up the site to industrial-level standards, but in an effort to work with the city, has agreed to clean it to a more stringent level.

However, to reach that higher standard, the project’s cost will go up. The cost for the difference between industrial-level and residential-level clean is something that DTE said will be covered through external funding sources and not passed along to ratepayers, Wiesemann said.

DTE Energy does not itself have plans to use the property at 841 Broadway St., which is currently zoned for industrial use; however, Ann Arbor officials have discussed possibly turning part of the site into a park. The property has an assessed value of $595,300 in 2012, down from $619,400 in 2011.

The city of Ann Arbor has delegated a task force to determine best future uses of the site and other properties along the Huron River corridor. The group is expected to make its recommendation at the end of December.

DTE is conducting a remediation project about 20 times larger than the Ann Arbor one at the Uniroyal site in Detroit on the Detroit River.

Throughout DTE’s work at the Broadway site in Ann Arbor, the company has had to be fairly flexible. The city had wanted to install two whitewater pools for rafters on the part of the river immediately adjacent to the site, but since they would have had to be removed as a part of the project, DTE has wrapped them into its overall project plan.

A camp of homeless people living on the western half of the site along the river also had to be removed this spring, Wiesemann said.

The project has left Wiesemann feeling more like a detective than an engineer at times.

“I’m excited to get under way,” he said Aug. 29 as he stood in a sunny portion of the site and surveyed the property. “We’ve done a lot of hard work and collaborated a lot with the city.”

The majority of the heavy construction on the site is scheduled for completion by the end of October.

Amy Biolchini covers Washtenaw County, health and environmental issues for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at (734) 623-2552, amybiolchini@annarbor.com or on Twitter.