Solar panels installed on University of Michigan land near Plymouth Road.

Joseph Tobianski | AnnArbor.com

Since University of Michigan President Mary Sue Coleman introduced ambitious sustainability goals 16 months ago, many practices have started to change at the school but there's even more left to do.

In the course of 12 months, the school introduced seven hybrid buses to its transportation fleet. It installed a 2.4-acre solar panel field on north campus and finalized plans for another large array to be constructed this spring.

The most expensive building U-M has ever constructed —the $754 million C.S. Mott Children's and Von Voigtlander Women's Hospital— received a silver LEED certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. Building to LEED code added tens of millions of dollars to the construction cost, but was consistent with the goals Coleman outlined when she announced a $14 million sustainability initiative in September 2011.

Coleman promised that all new major buildings would be LEED certified, that new dining halls would be trayless and that U-M would begin to embrace solar energy, despite the objections of naysayers.

She promised that by 2025, the school would reduce its waste by 40 percent, its greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent and its toxic runoff by 40 percent. By 2025, she said, all U-M buses would operate using sustainable technology.

All goals are measured from 2006 levels.

The goals are sweeping, and change has thus far been slow and incremental.

"It's going to take two, three or four years to really make a dent," Andy Berki, manager of the Office of Campus Sustainability, said of the goals. "They feel achievable, but they're challenging."

The university released its annual sustainability report on Tuesday.

Here's a by-the-numbers look at U-M's headway:

Solar panels off Plymouth Road.

Joseph Tobianski | AnnArbor.com

6 percent: The amount bus energy consumption decreased per passenger in 2012, according to the sustainability report.

At the same time, ridership went up by 538,000 trips, to above 7.4 million. Meanwhile greenhouse gas emissions per passenger decreased by 5 percent from 2011, according to the sustainability report.

That's partly due to U-M's gradual transition to hybrid buses.

The university added seven hybrid buses to its fleet this year. The 40-foot buses get about five miles per gallon of diesel fuel, a 30 percent improvement over conventional U-M buses, leading to an estimated annual fuel savings of $44,000.

Each bus costs about $518,000, or $175,000 more than conventional buses.

Meanwhile, U-M also added 30 hybrid sedans to its fleet this year and piloted a new bike rental program for students and staff. The school also is in the midst of exploring a bike sharing program with the city of Ann Arbor.

1,800: The number of solar panels installed on U-M's north campus near the intersection of Plymouth Road and Huron Parkway.

The panels, which span 2.4 acres, will soon be accompanied by a similarly sized spread off Fuller Road.

The Plymouth Road array, installed in fall 2012, produce 430 kilowatts, generating enough energy to power about 100 houses.

University of Michigan President Mary Sue Coleman announcing sustainability goals in September 2011.

Angela Cesere | AnnArbor.com file photo

The panels were announced by Coleman during her 2011 address. She warned prior to installation that she had already received negative feedback on the aesthetics of the planned field.

“What we are planning on north campus will be plenty visible,” Coleman said at the time. “I’ve gotten objections, and I’ve gotten people who have said ‘Oh they’re ugly.’”

The panels received a mix reaction from area residents, some who complained that they were an eyesore and others who praised them as an alternative energy source.

640: The number of U-M classes dealing with sustainability related subject matter, according to the sustainability report.

For sustainability to stick, education is key, officials say.

"We're focusing really hard on changing behavior on campus," said Don Scavia, special counsel to the president on sustainability and director of the Graham Sustainability Institute. "Most of us believe that technology is only going to get us [so far] and we really need to change people's behaviors in order to make a difference."

According to the report, there are 647 faculty members with academic and research backgrounds in fields relating to sustainability.

In March, the university, in partnership with Dow Chemical Company, launched a $10 million multidisciplinary sustainability fellows program, which is supposed to bring 300 scholars to Ann Arbor by 2018. Currently, there are 40 fellows representing 10 departments within the university.

684,400 metric tons: The amount of U-M generated carbon dioxide emissions in 2012, according to the sustainability report.

That number is well above U-M's 2025 goal of 510,000 metric tons.

Each year, U-M's campus and student body get larger and larger, forcing the university to be strategic in its goal of emissions reduction. The school has tweaked much of its major buildings and is exploring ways to increase the amount of natural gas it uses to produce energy.

"Growth and infrastructure continue to be a challenge," Berki said.

Levels, however, are an improvement from 2011, when U-M emitted 728,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas. In 2006 levels were at 680,000 tons, and U-M's 2025 goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent from that figure.

The year-old C.S. Mott Children's and Von Voigtlander Women's Hospital achieved LEED certification.

Joseph Tobianski | AnnArbor.com file photo

Overall, U-M emissions come 54 percent from purchased electricity, 45 percent from building operations and 1 percent from transportation options.

Since 2006, per-trip carbon emissions of U-M transportation options have decreased by 22 percent, according to the sustainability report. The school's 2025 goal is a 30 percent reduction.

28 percent: U-M's recycling rate in 2012, down 2 percent from the previous year.

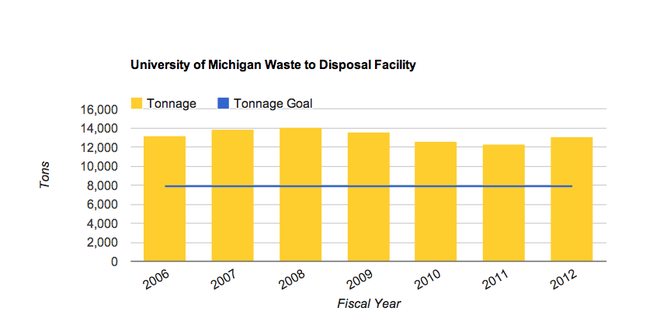

U-M produced slightly more than 18,000 tons of waste this year, up from nearly 17,400 tons in 2011 but down from a peak of 19,400 tons in 2009. Of the 18,000 tons in trash, about 13,000 tons went directly to landfills and about 5,000 tons were recycled.

Through the a recycling program at Michigan Stadium, 28 tons of recyclables were diverted from landfills during the 2012 football season, which included six home games. Recycling rates ranged from 13 percent to 30 percent per game. In 2011, during eight home games, nearly 41 tons of recyclables were collected.

During her 2011 address, Coleman pledged to reduce waste sent to landfills by 40 percent at U-M by 2025. According to the recent report, the school must still reduce waste by 39 percent in order to reach the 2025 goal.

"We're heading in the right direction, we knew when we set these goals that they were going to be difficult. They were defined as stretch goals for a reason," said Scavia.

"It was not going to be a smooth road toward them."

146 tons: The amount of food U-M composted in 2012.

Rob Doletzky, U-M grounds services supervisor, describes composting processes while at the composting site at Plant Building and Grounds Services.

Melanie Maxwell I AnnArbor.com file photo

In addition to pre-consumer composing, U-M piloted a food composting program in October, encouraging diners at the Michigan League to compost unfinished food.

Since 1997 U-M has collected 870 tons of compostable waste from six dining halls, two cafeterias and university catering, according to the sustainability report.

Meanwhile, to reduce food waste the university is transitioning to trayless dining. All new and renovated dining halls -including the soon-to-be-renovated East Quad— won't have trays. The hope is that students will gather less food, and thus waste lass. At least two U-M dining halls are already trayless.

The university creates its own fertilizer by composting plant material —such as flowers, leaves, grass— and mixing it with water, molasses and fish remains. The mixture is called compost tea and is used to maintain campus grounds.

The university is working to reduce the amount of chemicals applied to university grounds by 40 percent by 2025.

A University of Michigan chart tracking the amount of U-M waste that has been sent to landfills since 2006.

Kellie Woodhouse covers higher education for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at kelliewoodhouse@annarbor.com or 734-623-4602 and follow her on twitter.