Clik here to view.

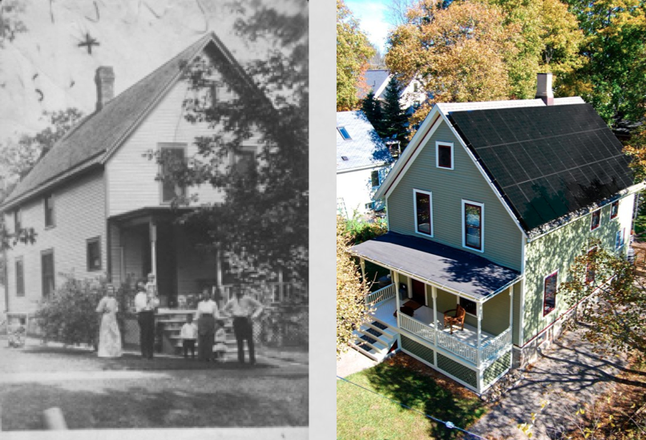

Shown above is a shot of the Grocoff's home as it was when it first was built, and a shot of house as it stands in 2013.

Courtesy of BLUElab team

Working with a team of engineering students from the University of Michigan, Grocoff hopes to find ways to collect, clean, purify and store enough water harvested on his property that he can unplug from the city’s water system.

It’s a goal, Grocoff said, that might not be possible.

“But it’s part of the larger question of finding a more complicated system of just having a centralized water treatment plant, a system we’ve used since the 1930s,” he said.

Ultimately, it could mean having a foot in both worlds — tapping into the city’s water system while at the same time of finding ways to capture and recycle water for daily use.

Unlike Grocoff’s net zero energy house where solar panels and other efficiencies produce all the energy his family needs, no one is claiming becoming net zero water is so easy. Grocoff and his wife, Kelly, restored their Old Folk Victorian house, making it the oldest net zero energy home in the country.

Clik here to view.

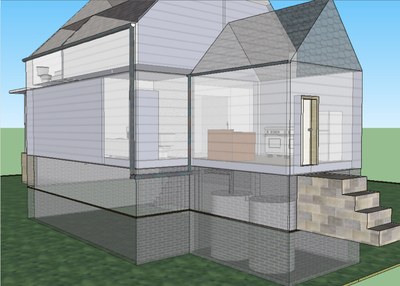

A mock-up of possible changes that could be made to the Grocoff house, including large tanks in the basement.

Courtesy of the BLUElab team

But capturing, cleaning and storing water is trickier than adding an array of solar panels to the roof of a house, said Steven Skerlos, professor of mechanical engineering and the faculty advisor for BLUElab, which stands for Better Living Using Engineering lab, the student organization working on the Grocoff project and an incubator for sustainable projects. “Between the time you capture water and use it, it can go bad.”

According to Grocoff, it’s time to find alternatives to an expensive and environmentally fragile municipal water system.

“Our current system won’t last beyond the life of my daughter, financially or ecologically," he said. "This house is just the beginning of the conversation.”

The BLUElab team is researching a number of ideas:

- Constructing a porous sidewalk that would act as the first filter for runoff water that would be captured underground, cleaned and stored.

- Collecting water that runs off the roof. This is complicated because most roofing materials, such as the asphalt shingles on Grocoff’s roof, are toxic. Students are studying rainfall data to determine how much water runs off the roof and its quality, said Devki Desai, the engineering doctoral student and team leader. “If, on average, you can collect 25 gallons a day from the roof and the average home uses 100 gallons a day per person, there’s a gap. You need to increase the catchment area and decrease use to shrink the gap.”

- A dual plumbing system could separate the gray water from the black water, Grocoff said. “We only need five to 15 gallons a day for drinking.”

- Storage is a challenge. With Michigan’s freezing winters, storage must be inside. But that consumes space. They are looking at building a system of round tanks in the basement, Desai said.

- They also are studying ways to filter and clean the water to potable standards, from an activated carbon system to resin filters.

- Compostable toilets, similar to ones at the U-M Dana Building, also are being considered.

- A number of ways to purify the water are being studied, Desai said, including UV rays, ceramic filters and using colloidal silver.

Implementation and construction are at least a year or two away, Desai said. Once her team has worked on the project and built prototypes, it will be up to Grocoff to find ways to finance the recommendations. “It would be hard to recover the costs,” Grocoff said. Water, after all, is relatively cheap to the individual homeowner. He hopes to convince manufacturers to use his house as a demonstration site to help defray costs.

The project will be registered with the Living Building Challenge, a certification program focused on the building industry.

The goal isn’t to return to an era of outhouses and hand-pumped wells, Grocoff said, even though his 1901 house had an outhouse in the yard, a hand-pumped well and a underground cistern. “I really want to emphasize that we don’t want to go back.”