The HVA bus at Michigan Stadium on Saturday.

Daniel Brenner I AnnArbor.com

Roger Simpson, who oversees HVA operations at the stadium, recalled a similar incident years earlier when another Notre Dame fan came to the HVA station and requested Tums. After asking him some questions and checking him out, they gave him the antacid and he went back to his seat. Near half time, the man had a cardiac arrest. HVA personnel shocked his heart with a defibrillator and he responded so well that when he awoke, he told them he had to get back to the game. When it was explained to him what had happened, the man finally relented and allowed himself to be taken to the hospital.

The point is not that Irish fans are overly enthusiastic about their team. Rather, that throughout the stadium on game days, HVA is handling dramatic events like these as well as minor medical needs.

Simpson, the vice president for HVA’s Central Operations in Washtenaw County, said he has 41 employees working at the stadium, including the four nurses and four paramedics staffing the first aid center. Mark Lowell, an emergency room physician at U-M hospital, and the one who treated Staudacher, is also there, along with three emergency medicine residents.

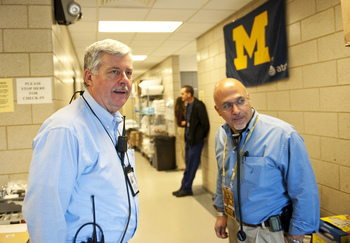

HVA Vice President of Central Operations Roger Simpson (left) in the First Aid building at Michigan Stadium on Saturday.

Daniel Brenner I AnnArbor.com

Simpson estimates that in the past 15 years there have been about five cardiac arrests in and around the stadium on game day. The more common reasons that people require treatment, though, are weather-related problems, drunkenness and chest pains. In early September, HVA staffers usually see 100 to 120 people per game because of the heat. But this year the cooler weather reduced that to 65. An air-conditioned U-M bus is made available on hot days for fans who are simply overheated.

In 2009, the university built a permanent facility along the northwest perimeter of the stadium, half of it for HVA and half for the police. Simpson has been working the football games since 1974, and said that at one time medical services were housed in an old schoolhouse inside Gate Eight equipped with tables, chairs and four rollaway beds.

"We now have 18 beds, plus a staff room," Simpson said. "Since the stadium becomes like a city within a city on game day, the facility has to be able to operate almost like a city hospital. There is also a mobile communications center outside the facility which is in contact with the first responders - the six mini-ambulances throughout the stadium and one on the field, and the 10 Red Cross teams.

Those mini-ambulances are John Deere Gators - utility vehicles that have been modified to handle stretchers and medical equipment. There are two people and an AED (automated external defibrillator) on each one.

The mini-ambulance near the playing field is seldom used. But if a player is seriously injured on the field, the team trainer will radio the mini-ambulance to pick him up and transport him to the locker room, where the team physician will attend to him. That Gator is equipped with an advanced life support system.

Of the roughly 100 medical incidents each week, about 20 percent are alcohol related, according to Simpson. "Those who are vomiting or incapacitated are taken to the U-M hospital emergency room," he said. "HVA parks five transport vehicles across the street on Keech for hospital trips." Those who aren’t as intoxicated and can walk are released to the custody of a family member or friend, but have to leave the stadium. Drinkers who are belligerent or are minors are turned over to the police and often are ticketed.

More from the Beyond Football series

Miss last week's story? Check out the links below for all the Beyond Football stories from this season.

- Michigan Stadium's turf is looking fine, thanks to Deaunna Dresch

- 'Officer Laura' in 4th year of directing U-M fans in front of Michigan Stadium

- Beyond football: What Michigan home games mean to Ann Arbor

- Beyond football: University of Michigan Marching Band keeps up the hard work - even during bye week

- Neighbors living in the shadow of U-M's Big House 'embrace Michigan football'

Simpson said that at the MSU and OSU games, alcohol-related incidents increase and make up half of HVA’s cases. Last year’s night game with Notre Dame was even worse, he said, because by the time the game started, people had been tailgating all day.

Simpson is a perfect fit for his job. He was a center on the River Valley High School football team in Three Oaks, in southwest Michigan, so he likes football. He also worked in the ambulance business growing up and is a trained paramedic. In addition, he worked with the Michigan State Police for 13 years before joining HVA in 1981, so he knows about the law enforcement side of handling some of the patients HVA sees.

He said he became a Michigan fan when he moved into the area, and misses being able to see the home games. "We do have a TV so we can catch the score occasionally, but we don’t have time to watch the game. Someday, though, I may surprise my wife and take the day off, get tickets, and take her to the game. She is an emergency nurse and works in our facility, too. Maybe we will even tailgate." So if you like to be surprised, Debbie, don’t read this.

Author’s disclosure: I wanted to write this article because of the importance of HVA to the stadium, to the city, and to the nine counties in southeast and south central Michigan that HVA serves. More personally, I wanted to write it because three years ago HVA, along with an Ann Arbor resident and the fire department, helped save my life after I suffered a cardiac arrest. And I’m not even a Notre Dame fan.

Bob Horning, a lifelong Ann Arbor resident, is writing U-M gameday stories for AnnArbor.com. If you have ideas for future columns, please email news@annarbor.com.