Students leave the Willow Run Intermediate School at the end of the day Friday.

Courtney Sacco I AnnArbor.com

Nov. 6 promises to be defining moment for administrators at both districts. Regardless of whether residents vote "yes" or "no" on the question of consolidating the two financially struggling school districts, the results of this election will have far-reaching effects.

If the unification passes, administrators say it will wipe the slate clean by giving them more time to pay off the districts' crushing debts and the opportunity to develop a new school system with more successful programs.

If it doesn't pass, both districts face a host of possibilities, including more state cuts and state emergency financial managers.

Combined, Ypsilanti and Willow Run schools have more than $15 million in debt. Willow Run has been climbing in and out of the hole for the past seven years, whereas Ypsilanti’s deficit has grown substantially since 2009.

In the academic arena, both districts have graced several of the state’s “lowest achieving” lists, have below average graduation rates and are bleeding students and staff.

The teachers and students have the most at stake in the proposed merger, despite students not being able to vote. In total, there are 4,685 students whose lives will be impacted by the outcome of the vote. Some may end up going to different schools and programming changes are likely if the merger passes. Teachers have been educating students on the potential outcomes of the merger, and some have used it to teach civic engagement and responsibility.

Fear of the unknown has plagued many stakeholders throughout the process and none have been more concerned than the districts’ teachers who could lose their jobs and endure cuts to pay and benefits, regardless of the election's outcome.

Campaign leaders have found people, and especially staff, in the Willow Run school district are more reluctant to support the merger proposal than people in Ypsilanti, although there is no organized opposition to the effort.

The ‘ugly stepchild’

For many voters and Ypsilanti-area residents, consolidation is not their first choice, but rather the best option they have.

“I’m a real advocate of public education. And for that reason, I don’t want to see either school district just go down,” said Lavada Weathers, a lifelong community member whose family has been in the Willow Run School District since World War II, when the Willow Run schools were first established to educate the children of workers at the Ford, B-24 manufacturing plant.

“All we can really do is vote and pray that it’s all going to work out.”

Weathers and her husband, E. L., are the perfect example of how the two districts are “a lot more intermingled than we think we are.” E.L. graduated from Ypsilanti High School in 1958, while Lavada graduated from Willow Run High School. Their youngest daughter went to Ypsilanti and their grandson went to Willow Run.

“It’s all in the family in Ypsilanti and Willow Run,” Lavada Weathers said.

Despite her concerns about the consolidation, Weathers has helped lead a group of parents and community members from both school districts in the campaign effort. She assumed the role of co-chairwoman of the Friends of Education Committee, a group that has existed in Washtenaw County since 2009 and been active in other non-partisan, school-related campaigns, according to the county’s website. This election season, the committee has been working for the passage of the merger.

Recent campaign finance filings show the Friends of Education Committee received 25 campaign contributions, totaling $2,659. The filings also show the group spent $8,348.94 on pamphlets, fliers and mailings.

The committee had a balance of $6,447.69 from previous activity, so it currently has $757.75 in cash at hand.

Residents in the Ypsilanti and Willow Run school districts will weigh whether or not to consolidate the two struggling districts on Nov. 6. What will become of the districts' high school buildings, Willow Run at left and Ypsilanti on the right, will not be decided until after the vote.

AnnArbor.com

“I tell people who are against it that the bad part about all this is, if we don’t vote to do it, it’s really going to be chaotic — especially if the state comes in and takes over,” she said. “If we go with consolidation, we still get to fight for what we want. The staff, the curriculum

“We’re scrappers in Willow Run. We’ll get what we want,” she said with a chuckle. “But if we let the state take over, we’ll have no voice. We’ll be stuck.”

Weathers said she found while out educating people about the merger proposal that the teachers and community members in the Willow Run district are less supportive of the merger than those in Ypsilanti.

People cited reasons such as a rivalry between the schools, concern about Willow Run’s new “beautiful” high school and middle school being closed, and a belief that the unified district will not be able to “work quickly enough” to improve student achievement and attract more families.

Blake Nordman is one Willow Run teacher who lives in the district and will be voting no on the consolidation Nov. 6, he said.

For him, the biggest factor is the difference in Ypsilanti and Willow Run’s debt. He said Willow Run’s deficit in the beginning was about $4 million. It is now about $2.8 million. Ypsilanti’s deficit, on the other hand, has grown from about $4 million to about $13 million, he said.

“Our finances are actually getting in order. We did well on the state testing this year. We’re in safe harbor in comparison to Ypsilanti,” Nordman said. “ (Ypsilanti’s) projections are going up. They are the ones really, really in fear of being taken over by the state.”

In Nordman's 14 years as a teacher at Willow Run Community Schools, he said he’s seen frequent turnover in teachers, principals and superintendents, and some “very poor, top-down financial decisions” be made.

While Nordman said Willow Run is far from perfect, he believes the district is finally on the right track. And in part, he credited former Superintendent Doris Hope-Jackson.

Hope-Jackson’s leadership was “combative” and not exactly a “shining moment” for the district, Nordman admitted. But he said she came in focused on balancing the budget, made some “drastic, crazy cuts,” closed several buildings and established the primary, elementary, intermediate and high school programs the district has now.

“It cost us a lot of students probably, but in the long run it’s made the difference,” Nordman said.

He said there is a longstanding rivalry between not only the students, but also the adults, in the Ypsilanti and Willow Run districts. He said mostly the rivalry is just talk, and while there have been a few fights, most were a “long time ago.”

“This community is very tight-knit and family-oriented. We have a long and proud history from the Willow Run plant being built here in 1942, the B-24 bombers and Rosie the Riveter. We just celebrated our 60th-year anniversary a few years ago,” Nordman said. “There are adults in the community who feel like we (Willow Run schools) have always been the ugly stepchild of Ypsilanti’s.”

Washtenaw Intermediate School District Superintendent Scott Menzel said he is aware that some among Willow Run’s staff share Nordman’s attitude toward the merger. However, he said when making an argument about the district’s deficits it is most accurate to look at it in terms of percent of the overall operating budget. Menzel said Willow Run’s deficit is about 14 percent of its budget and Ypsilanti’s is 17 percent of its budget.

“So when you frame it from the point of expenditures, they’re really not that far apart,” he said.

Fear, denial and life lessons

For Ypsilanti New Tech teachers George Lancaster and Christa Dolan, the reality of their own fears about the merger did not sink in until they were forced to address their students’ concerns.

The two educators led their 11th-grade CiviStat class, a hybrid course that combines government, economics and statistics, in a research-based project on the consolidation.

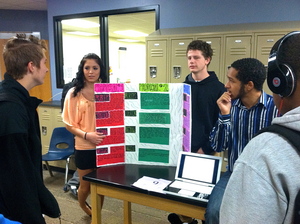

Students present their project weighing the Ypsilanti-Willow Run merger proposal at New Tech High in Ypsilanti in early October.

Courtesy photo

At the start of the effort, before information had been thoroughly and repeatedly discussed, all of the 24 groups were decidedly anti-consolidation.

Most of the students in the class knew nothing about the merger proposal. Bree Marich knew the idea had come up and that both districts are in debt, but the extent of Ypsilanti’s money problems shocked her, she said.

“We heard rumors about combining Ypsilanti and Willow Run,” Marich said. “But I thought they were rumors. My first thought was ‘I don’t want this happening.’ We’re rivals.”

Fellow New Tech student Shelby Olvera said when she heard teachers and staff at Ypsilanti might not be paid due to the district’s budget deficit, she immediately became worried.

“I was scared because I didn’t know who would teach us,” she said. “ If I wasn’t going to get paid, I wouldn’t go to work.”

“It was jarring,” Dolan said of her students’ reactions to the news of the possible merger and the districts’ financial problems. “Some of them really freaked out on us. There were a lot of questions.”

“We saw people mad and outraged more so than afraid,” Lancaster said. “It was definitely a challenge to get them to listen at first and to learn about it.”

Dolan said some students in the class had just left Willow Run this fall to come to Ypsilanti. “So naturally they didn’t want to go back when they just got here.”

The idea behind the project was to have students learn all they could about the potential merger and the arguments on both sides. Students then were asked to present their case for or against the proposal to New Tech’s underclassmen.

By the end of the project, just four groups of students retained their “no” stance toward consolidation.

Dolan stressed that she and Lancaster both encouraged their students to pursue whichever side of the merger proposal they felt most strongly about — as long as they could support their arguments.

Olvera and Marich said what changed their minds about the consolidation was the fact that programs and sports continue to be cut at Ypsilanti, and joining with Willow Run could mean more opportunities, better sports teams and the expansion of New Tech’s program, which they both love.

All of Willow Run High School currently employs the New Tech model. This curriculum was adopted at Willow Run after the high school found itself on the state’s lowest performing schools list in 2010.

Juniors at Ypsilanti New Tech High School present projects on the consolidation proposal to underclassmen earlier this month.

Courtesy photo

Despite intending the project as a lesson in civic responsibility for the students, it quickly became a learning experience for Lancaster and Dolan as well.

“We spent a lot of time talking to them about what could happen and what we knew and didn’t know. How as teachers, we had to do a lot of trusting. It really became eye-opening for us, too,” Dolan said.

Lancaster said he has thought for a couple of years now that consolidation was something that would have to happen.

“I just didn’t think it was possible. That people at both districts would actually agree to it.”

The districts are small enough and geographically close enough that it makes sense from a location and capacity standpoint, he said, adding he always thought it “a bit much” that the community of Ypsilanti had two school districts to begin with.

“(The consolidation) doesn’t make me nervous, per say, but I also have questions about the programs and the buildings that will stay,” he said. And of course, job retention is a concern.

Teachers at both districts have been told they will have to reapply for their jobs, if the consolidation passes, and pay likely will be reduced. Teachers in districts already have taken drastic pay cuts in the past few years. Nordman said he makes about $5,000 less than he did a few years ago.

Lancaster said he’s not going to pretend he hasn’t looked for other jobs.

“I would guarantee most of us at both districts have looked. We’d be foolish not to,” he said.

Dolan said these are the types of honest, raw conversations they’ve tried to have with their students.

“It meant something for us to say to them that we could lose our jobs. The fact that even the adults don’t have all the answers and don't know what's going to happen was somehow reassuring to them,” she said.

Lancaster added it’s a good life lesson for the students because soon they will be choosing colleges and choosing careers and making other tough decisions without always knowing precisely what the outcomes will be.

“We can’t always look at the big picture, at 10 years from now and know what's going to be best long-term,” he said. “Sometimes you have to just take that leap. And if it doesn’t go the way you thought, you have to deal with it.”

Interest from afar

The consolidation proposal has garnered attention from educational communities across the state, as well as Michigan Superintendent Mike Flanagan and several local legislators.

State Superintendent of Schools Mike Flanagan came to town to praise Ypsilanti and Willow Run school district leaders for being trailblazers at a meeting in August at Eastern Michigan University: "I think you can be a model for the rest of the state," he said.

Danielle Arndt | AnnArbor.com

Menzel has said repeatedly, “This cannot fail.” He and other supporters are adamant unification is the only way for both districts to avoid an emergency financial manager and to secure additional funding to provide the best educational options for students.

“We cannot allow the number of students that have been unsuccessful at both of these districts to continue to be the case,” he said.

If the consolidation passes, it would be the first time in state history that two financially and academically struggling districts have merged in an attempt to solve both problems.

Undoubtedly, school officials from other deficit districts would be watching for signs of success or failure during the consolidation effort, waiting to determine if consolidation is in fact a viable option to solve their own budget or achievement woes, Menzel said.

“The pressure will not be off.”

But if the consolidation fails, people still will be watching, and those from the state perhaps even more closely.

Both Willow Run and Ypsilanti have far exceeded the state’s two-year timeframe for bringing their fund balances back into the black. In addition, Ypsilanti’s looming inability to pay teachers and staff could trigger a preliminary review by the state, the first step toward an emergency financial manager, according to Public Act 4.

Whether the consolidation passes or not, Ypsilanti Superintendent Dedrick Martin has said he’s not sure how the district will pay its staff come January.

Martin Ackley, spokesman for the Michigan Department of Education, said in July that none of the steps required to appoint an emergency manager had been initiated with either Ypsilanti or Willow Run. However, financial reports for the 2011-12 academic year are due in November and further assessment of districts’ financial situations will be done at that time, Ackley said, adding “each case is determined on its own merits.”

Michiganders recently saw the Highland Park and Muskegon Heights school districts dismantled by emergency managers. Both were transformed into charter school systems, had their assets liquidated and buildings closed and watched as their financial managers selected the management companies to run the charter schools and established boards to oversee them.

Menzel said consolidation is the best way for residents of both districts to maintain control of educating their children in the manner they see fit.

- Read more stories about the proposed consolidation of the Ypsilanti and Willow Run school districts.

Danielle Arndt covers K-12 education for AnnArbor.com. Follow her on Twitter @DanielleArndt or email her at daniellearndt@annarbor.com.