Related story: Michigan Stadium will be open Sunday to 'heroes' during massive donor registration drive

As a 29-year-old first-time mother, Jasmine Huang watched as the skin of her 5-month-old daughter slowly yellowed with jaundice.

Clik here to view.

Huron High School senior Shiahan Huang received a liver transplant at the University of Michigan at the age of 2 that saved her life. Born in Taiwan with a severe form of biliary atresia, doctors initially did not have a good prognosis for Shiahan. Pictured here with her scar Thursday at her Ann Arbor home just days after her 17th birthday, Shiahan said she wants to pursue a degree in the medical field to help others.

Joseph Tobianski | AnnArbor.com

Living in Taiwan in 1996 where the hospitals weren’t equipped or accustomed to perform transplants on infants younger than one year old, doctors told Jasmine and Joseph Huang that the likelihood of a new liver for Shiahan was not good. The condition their baby girl was born with would likely be fatal.

Fast forward to the present: Shiahan (pronounced "shee-hon") turned 17 this October. Braces. Glasses. College applications. The hallmarks of growing up.

Thanks to the sacrifice of her own family and of a family she’s never met, the once small, sickly girl is now a thriving teenager and a senior at Huron High School in Ann Arbor.

Shiahan is among the thousands that have received life-saving transplants at the University of Michigan Health System.

There are 2.9 million Michigan residents registered to be an organ donor and 3,082 people are waiting for a transplant in the state, according to Gift of Life Michigan. About 344 of those people are specifically waiting for a liver.

For critically ill individuals like Shiahan, it only took one match to save her life -- a debt that both Shiahan and her parents feel almost burdened to repay.

When Shiahan was born, the Huangs were in a state of flux themselves: Joseph was trying to complete an engineering degree at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and Jasmine had traveled back to her family in Taiwan just to have her baby.

Jasmine said it was difficult to find donors because the body of deceased individuals is viewed as sacred in many Asian cultures -- especially when it comes to children and infants.

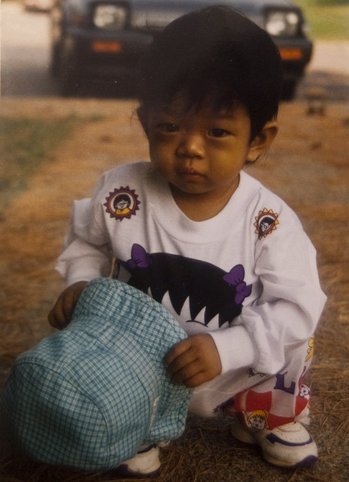

Clik here to view.

Shiahan Huang at the age of 2 in October 1997 before receiving a liver transplant at the University of Michigan.

Courtesy of the Huang family

While she waited for a match, Shiahan’s jaundice progressed. She was smaller than the other children, and her stomach was abnormally large as her liver swelled.

Five days after Shiahan’s second birthday, the call came. An available liver had been found.

Jasmine said she was both elated there was a solution and terrified to know her daughter would get the surgery -- because if it failed, there was no other option.

A month after the surgery near Thanksgiving 1997, Shiahan’s body fought against the new liver and the family headed to the hospital. A month later, near Christmas, her body tried to reject the liver again.

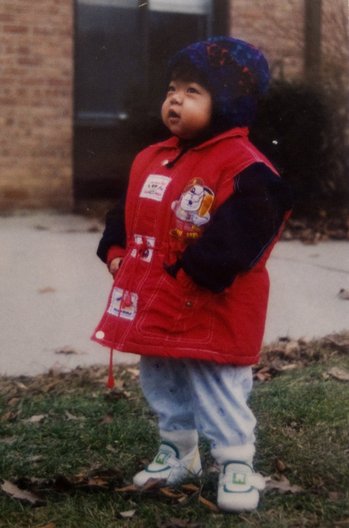

Clik here to view.

Two-year-old Shiahan Huang months after her liver transplant in February 1998, when her health was dramatically improving.

Courtesy of the Huang family

The Huangs had another daughter, Jewel, who is five years younger than Shiahan. Life in and out of the hospital to care for Shiahan’s liver became the family's new normal.

Though the Huangs have no knowledge of the family of the child whose liver is thriving inside Shiahan, Jasmine Huang is still overcome with emotion when she reflects on their sacrifice.

“I always wanted to say thank you to those parents,” Jasmine Huang said, as tears quickly welled up in her eyes as she thought of them. “Their kindness and selflessness it’s such a gift.”

Living with the knowledge that she would have likely died without the liver transplant, Shiahan grapples with the brevity of how she will be able to give back to the world.

“Why me?” Shiahan said. “A lot of other kids probably needed it too I need to find out why I was given a second chance.”

Disease often fatal

Dr. Jeffrey Punch is the head of transplantation at the University of Michigan Health System. He performed the liver transplant surgery on Shiahan early in his 18-year career at U-M.

Clik here to view.

Jeffrey Punch

“Fortunately, liver failure is really an uncommon problem for children,” Punch said, explaining that while the number of adults that need liver transplants has increased, the number of children that need livers has stayed constant.

Biliary atresia is fatal, Punch said. Three-fourths of the children with the condition die by the age of 6, and some live to be teenagers. Many of them die within their first year, Punch said.

“It’s a puzzling disease and we don’t really understand it,” Punch said, explaining the only long-term solution is a liver transplant.

At the time of Shiahan’s surgery, liver transplants in infants were a common procedure at UMHS, Punch said.

The transformation in sick children that receive liver transplants is “phenomenal,” Punch said.

“In many fields of medicine, the good work you do is not as dramatic.”

Hope after surgery

Shiahan has very few limitations: She’s an active member of the crew team at her high school and she figure skates.

But the reminders of the liver transplant Shiahan received at the age of 2 come daily: She takes seven pills to keep her immune system from turning against the foreign organ inside her body. And every time she gets dressed, her shirt falls over a half-moon-shaped scar across her entire abdomen, high above her belly button.

As a young child, Jasmine Huang said Shiahan would show off her scar to whomever she could find to try to scare them. But as Shiahan grew older, it made her more and more self-conscious.

It wasn’t until Shiahan went to Camp Michitanki -- a summer program for children that have received transplants -- that she came to fully accept the scar for what it represented.

Learn more about organ donation

Shiahan applied early decision to the University of Michigan. There’s no question in her mind that she wants to work in the medical field, as she’s been around doctors, nurses and needles since she can remember -- though she still is uncomfortable receiving shots, she said.

“For the person whose liver I have, I consider them whenever I make an important decision, instead of just thinking about myself,” Shiahan said.

The Huangs are both organ and bone marrow donors themselves, and Jasmine -- who has a degree in Chinese literature -- works in the University of Michigan’s medical interpreter program. When families come to the U-M hospital who can’t speak English, Jasmine helps them navigate the litany of medical terms and procedures.

The lifespan for a liver transplant is typically about 10 years, Dr. Punch said. Patients that receive transplants as children typically have better outcomes, but there’s no way of knowing how long a transplanted liver will last.

“The transplant system tries to prioritize them so they don’t die waiting,” Punch said.

Jasmine Huang said she doesn’t know how long Shiahan’s liver, now 15 years old itself, will stay healthy. But Shiahan’s future is something Jasmine has come to fiercely defend.

“As long as she is alive there is hope,” Jasmine said.

Amy Biolchini covers Washtenaw County, health and environmental issues for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at (734) 623-2552, amybiolchini@annarbor.com or on Twitter.