Ann Arbor resident Glenn Dickerson vividly remembers the 37 months he served during World War II. The experience was one that produced memories he will never forget.

Dickerson, who will be 90 next March, has been named Knight of the Legion of Honor by the Consulate General of France and will receive a medal Tuesday for his extraordinary bravery in helping to liberate France during the war.

"I’m flabbergasted and awed of course," Dickerson said. "There's not many of us left and it's a way of them honoring us all before we're gone. I’m very proud to wear it and I feel that it will serve as a display and reflect the honor and the integrity and the courage of all of the 121st engineers. It's not mine, I’m just representing them."

June 12, 1944: The day it all began

Dickerson was drafted in February 1943 as a Private First Class and served in the 121st Combat Engineers with the 29th Infantry Division. He first arrived on Omaha Beach, June 12, 1944, six days after the D-Day Invasion, when 160,000 Allied troops landed in Normandy to fight the German forces. American forces landed on Utah and Omaha beaches.

Dickerson was part of a replacement package, which was designed to bring the combat units back to strength by replacing the many casualties of the first few days of the war.

"They knew pretty well what the casualities would be so they put them in packages of so many engineers, so many infantry, so many artillery men, and even a chaplain or two," he said. "Men who would no doubt be casualties on D-Day."

A bout of pneumonia caused Dickerson to miss being part of the first wave of soldiers who arrived on that fateful day of June 6, when more than 9,000 Allied soldiers were killed and wounded.

"We got in the war pretty quickly and our engineer outfit was plugged into the front line to hold it until other replacements could come along and beef up the infantry casualty problem," Dickerson said.

His first few days there, Dickerson said German planes dropped bombs on their position.

"We were constantly harassed by snipers," he said. "They seemed to know where we were, but I never saw even one of them. Our engineer officers were not very well trained in infantry tactics and we did suffer more casualties."

Dickerson recalls the nights when he and others had to find a place to sleep to protect themselves from enemy fire. The soldiers dug themselves into foxholes, small dugouts with pits for individual shelter against enemy fire, and hoped they made it through the night.

"A soldier I never met before, Marvin Gutknecht, who became my foxhole buddy, invited me to join him in his foxhole because then we’d have two blankets and we’d be warmer so of course I did," Dickerson said.

Marvin Gutknecht, left, and Glenn Dickerson, right, were close friends during and after WWII.

Courtesy Glenn Dickerson

That move, according to Dickerson, saved his life.

At dawn, the Germans hailed down a barrage of 88mm shells and heavy mortar fire, most of which landed in the area where his squad was in.

"During the night, a new replacement arrived at the area and was told to just find any place," he said. "So he wondered around and found my empty hole and the next morning, the German artillery opened up and put a shell right on top of that foxhole that I was to occupy and killed him.

"For the rest of the war, Martin and I dug in together and whenever they needed two or three men on missions, we kind of volunteered together."

Dickerson said it haunts him to this day that he never found out who the man was that lost his life that day.

A long, deadly path

The two were inseparable after that night. On July 18, 1944, their division made its way toward St. Lo, a commune in northwestern France.

The path there was long, arduous and deadly.

"The Germans were really entrenched there," he said. That was a big rail center for their supply lines and it took us a long time to get it."

Along the path, the division encountered hedgerows, which were built by French farmers. Hedgerows were comprised of walls 3 or 4 feet walls thick with rocks, dirt and shrubs. The hedgerows slowed their progress considerably.

"A tank could not blast through them, and German artillery and other fire powers were centered on all of the lanes leading to crossroads and we had to get through the hedgerow somehow," Dickerson said.

As an engineer, Dickerson was tasked with using explosives to remove obstacles, laying and removing mines and blowing up various things.

Since the tanks couldn't get through, the engineers came up with a design to break through the hedgerows to gain ground.

When the tank punched into the hedgerow, it left two neat holes deep into the hedgerow and the engineers prepared custom explosive devices that fit in the holes, Dickerson said.

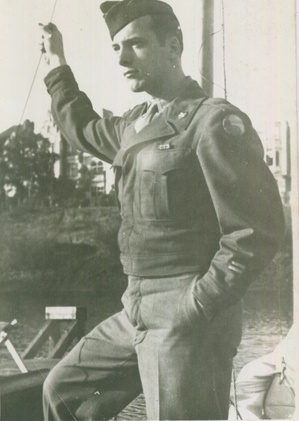

Glenn Dickerson in an undated photograph.

Courtesy Glenn Dickerson

"Under one arm we followed the tank as it punched the holes in the hedgerow," he said. "The tank backed off as we ran around to insert the explosives, one in each of the two holes, tied the primer cords together with blasting caps and five second fuses and ducked behind the tank."

The explosion tore into the hedgerows and allowed the tanks and infantry to dash through.

Dickerson, Gutknecht and several others were awarded a Bronze Star, an individual military award designed for the United States Armed Forces, for their acts of heroism and merit. The U.S. has credited their division with developing explosives to destroy German defensive lines and allowing Allied tanks to advance.

In August, Dickerson began clearing out roads close to Brest, France in preparation for the placement of big guns that were to be used in shelling the German positions around the city.

Dickerson was tasked with sweeping the area with mine detectors. Dickerson's son, Norman, said his father told him the Germans were known for burying mines far into the ground.

"It would be so far down and a whole bunch of guys could walk over it," Norman said. "The idea behind that is they were waiting for enough weight to set it off."

Dickerson said one day his team thought everything was cleared out, and as a transport vehicle came down the road with some Americans in it, he and Gutknecht were on the side of the road.

"It went off and blew the truck up," he said. "There were casualties involved ... ."

It was a hard lesson learned and one that cost some their lives.

"We all felt responsible but we didn't know what more we could have done ...," he said. "I'm sure Marvin felt as responsible as I did, but we never discussed the episode again."

The push to St. Lo was something that Dickerson will never forget, as that was when many individuals he knew died.

Glenn Dickerson and Marvin Gutknecht protected one another throughout the war.

Courtesy Glenn Dickerson

"Somewhere on the push to St. Lo, the registration boys came in to collect the bodies and they were all over the place," he said. "They pulled up a Jeep with a trailer and started loading them. It looked like someone was loading a bunch of cordwood."

Dickerson said war movies such as, "Saving Private Ryan", are all somewhat realistic, but there's one thing that cannot be mimicked.

"The thing they can’t depict or repeat or duplicate on the screen is the smell," he said. "The combination of rotting flesh and burned powder is a smell you won’t forget. A lot of things remind you of it and you just stand still and try to calm yourself. Once in awhile I get a whiff of something that reminds me of it."

Dickerson said that memory is something that was engraved in his mind and affects him to this day.

"I have a friend that I visit in Manchester and one day we went to a sandwich shop with a large window," he said. "This particular day, here comes a Jeep and he’s hauling a load of cordwood and I looked out and for less than a second that trailer was a trailer loaded with bodies.

"I saw the bodies and I smelled it just for a fraction of a second and it was gone. I took another look iand it was just a jeep with firewood... It stays with you."

A friendship forged forever

When the war ended in 1945, the friendship between Gutknecht and Dickerson continued. Dickerson came back to Michigan and obtained his bachelor's degree from the Michigan State Normal College, which is now Eastern Michigan University, and his master's degree from the University of Michigan. After college, Dickerson taught in the Ann Arbor Public Schools system for 40 years at Tappan Elementary and Forsthye Middle School.

Dickerson went on to have two children, Norman and Matthew, with his wife Kathleen. They were married for 54 years before her death in 2000.

Gutknecht returned to Oshkosh, Wis., but the two tried to keep in touch through letters. At some point — Dickerson can't quite remember when — the two lost contact.

Glenn Dickerson and other members of the military.

Courtesy Glenn Dickerson

Gutknecht died almost 10 years ago.

"Marvin was unflappable and took things as they came," Dickerson said. " I’m not saying I couldn’t have gotten through the war without him, but he was quite the support and I will never forget him."

One of Gutknecht's daughter's, Kay Gutknecht, become very interested in her dad's time in the military, but while he was alive, he didn't talk much about it.

"My dad got Alzheimer's when he was in his mid 60s and unfortunately, my dad was in a place where he didn’t remember enough," Kay Gutknecht said. "I read a few things to try to understand what he went through, but it wasn’t until we found Glenn that we did."

Dickerson sent Kay Gutknecht a narrative of their time served as well as hundreds of letters they shared with each other. Kay's family was so happy to receive them that she compiled them into a 1,100 page book that included photos. The book, "We Were Foxhole Buddies," took about three years to complete.

Twenty copies exist with several of them at museums around the country, including the National Library of Congress and the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

Shortly after this, Kay Gutknecht heard that the French Consulate was awarding living WWII veterans with the country's highest award, the Legion of Honor, which was created by Napoleon.

I put together a letter to the French Consulate of Chicago and said I think he deserves the medal and here’s why," Kay said. "I would feel like my dad had gotten it too and not just for us, but others who are already gone that deserve the recognition too, but can't get it. People like my dad who made it through the war and aren’t alive now. They all did it together."

"Thanks to their courage, to our American friends and allies, France has been living in peace for the past six decades," said the consul general of France Graham Paul in a statement. "We shall never forget."

In addition to the Legion of Honor and Bronze Star, Dickerson has received the European, African, and Middle Eastern Service Medal with four Bronze Stars, the American Theater Ribbon, the Good Conduct Medal and the WWII Victory Medal.

Liz Mannebach, press assistant for the Consulate General of France, said about 100 veterans within the Chicago Consulate's jurisdiction receive an award per year, although the numbers have decreased over the years. The Chicago Consulate oversees 13 states.

"It's a finite number of men who serve that are eligible," Mannebach said. "We awarded 66 medals in 2011. We attend about 10 to 15 of the ceremonies where we actually go and pin the medal on the veterans."

Glenn Dickerson

Courtesy Glenn Dickerson

Dickerson often reflects on what receiving the award means and how important Veterans Day is for not just those who served, but the country.

"The veterans who are still alive will reflect on how lucky they are to still be alive because so many of their friends were killed and wounded," he said. "The fact that we are still alive and came back, it's not a feeling of being grateful.

"It’s feeling the sacrifice of others. What contributions they could have made if they still lived. The ones who did live have to think about the guys who took the bullet when you didn’t. I’m so sorry for them that they didn't make it."

Tuesday, Nov. 13, the Deputy Consul General of France, Francois Pellerin, will travel to Ann Arbor to present Dickerson with his medal. The ceremony will be held at Weber’s Inn at 3050 Jackson Ave., at 2:00 p.m.

Katrease Stafford covers Ypsilanti for AnnArbor.com.Reach her at katreasestafford@annarbor.com or 734-623-2548 and follow her on twitter.