“I wanted to know, ‘What do I really have to do?’” said Halperin. “ What more do I have to do besides having sex with people? Isn’t everything else just a cliche or a stereotype?”

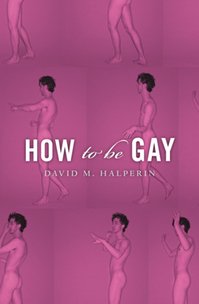

To answer this question—about the intersection of sexuality and culture, and how gay men teach each other "how" to be gay, culturally speaking—Halperin created a U-M course called “How to be Gay,” as well as a recently released book of the same name that’s now gaining national attention.

The book begins with the story of how and why Halperin’s class, months before it even started, became a national lightning rod for controversy: An editor at U-M's The Michigan Review alerted The National Review to the course offering in the spring of 2000, and when the NR published the course listing on its website, critics swarmed to condemn what was viewed as an “indoctrination” course.

“The political organizations that were using my class to foment a lot of outrage against the University of Michigan really had an interest in not communicating to people what the class was about, but as portraying it as something completely, absolutely outrageous,” said Halperin. “Something that no proper university or any decent professor would have taught to begin with. That this was a class designed to convert straight students to the gay lifestyle. And they didn’t really care if this was true or not.”

U-M stood by Halperin, fielding countless emails and calls, while Halperin responded to messages and accepted a few media requests for interviews.

“I only accepted to do interviews when I thought that I would in fact have a chance to explain what the class was about, rather than simply to be made the object of media sensation, or provide an opportunity for opponents of the class to get a lot of airtime,” said Halperin.

The frenzy finally dissipated, and over the next few years, Halperin taught the class five times before deciding he’d satisfactorily answered, for himself, the questions that gave rise to the course, and thus had what he needed to write a book.

And “How to be Gay” has received some high-profile coverage since its release, including a generally positive review in The New York Times Book Review. But Halperin has been disappointed that “there has not been a single extended mainstream review that has contained an accurate summary of the book.”

David Halperin

"I’m not looking necessarily for praise or agreement, and I’m not opposed to or upset by controversy. In fact, I like to have an argument with people about stuff that matters. What surprises me is that people seem to be taking issue with a book that doesn’t exist, and that I didn’t write. So that makes me think I may have hit a topic that is important.”

Halperin’s book discusses how the 1969 Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village helped establish and mobilize gay communities, while also sparking a new wave of sexual openness within them. Because for many years, Halperin argues, silenced, closeted gay men had previously clung to certain films, musicals, torch singers, etc. for the purposes of vicarious self-expression, post-Stonewall gay men publicly eschewed these gay cultural touchstones, having supposedly been freed of their need for them by way of publicly owning their sexuality.

Halperin notes, however, that these cultural works quietly remained deeply entrenched in gay male culture, and the book explores why, if there was no longer a need for them, they continued to be important to gay men. Halperin’s answer, in part, is that when gay male sexuality was released from its closet, gay cultural touchstones were simply tossed into the closet in its place. But the link between sexuality and cultural subjectivity is one that may be far more complicated than many would like to believe.

“People get so hysterical at the very idea that there might be such a thing as a gay culture, or that there might be a cultural difference between the gay world and the straight world, or that there might be some association between gay male culture and some kinds of gender dissonance or deviance, not to say femininity,” said Halperin. “The very mention of this gets people apparently so upset that that they don’t stick around long enough to consider what I’m actually saying, or they look at the book and they impute to me all sorts of views that I’m not propounding.

"I’m interested in understanding an absolutely contemporary problem, which is, what does sexuality have to do with cultural form? That’s the problem now. It’s a problem that has to do with why gay men now would have created such a cult around Lady Gaga, say, or around certain kinds of aesthetic practices or values, whether it’s design or fashion or certain kinds of music.”

According to Halperin, no existing theory could adequately be applied to the intersection of sexuality and cultural form, so in “How to be Gay,” Halperin aims to create a new theory and apply it to some cultural examples—like Joan Crawford—in detail.

“What my analysis implies is that one way to explain gay male culture’s investment in some of these figures is to say that gay culture is responding to certain hierarchies of gender and sexuality that pervade the cultural field,” said Halperin. “That there are still—we sometimes don’t like to believe it, but there are forms of social inequality and social stratification that have to do with the relations between men and women, and masculine and feminine, that have not gone away, and that have structured or have pervaded all of culture, so that we find these iniquities, these gender asymmetries, reappearing in such things as the value of tragedy and the value of melodrama, or the meaning of certain kinds of sentimentality, or the value placed on certain kinds of emotion and emotional expression.

"But these things are in fact gendered. Sometimes sexualized, but especially gendered, and the gendering of them creates a culture which is simply unjust in its treatment of women and people who are marked as feminine, and of people who are also marked as not heterosexual. That a lot of what I describe in gay culture represents a response to this, an attempt to appropriate some of this material so as to resist it and make it into a vehicle for contesting these gendered and sexualized meanings.”

At the end of the book, Halperin argues that the disappearance of gay culture isn’t a result of the mainstream’s growing acceptance of gay people, but rather the destruction of gay communities.

“We’re living in a period of great triumphalism about the success of the struggle for gay rights, with gay marriage being the prime example,” said Halperin. “And the notion is, we are on the verge of a major historical transformation in U.S., with the complete social integration of gay people into society at large. The very existence of gay culture in such a context seems like a threat to this story that we’re telling ourselves of the total assimilation of gay people into mainstream society. And so people don’t want to think about it at all. It seems like a completely retrograde topic. But what makes (gay culture) seem retrograde is not the fact that gay culture is or is not dead. What makes it seem retrograde is that gay people nowadays no longer have a choice to live in any other way but dispersed among straight people in mainstream society.”

Halperin might be viewed as both an insider and an outsider, given his status as a “bad” gay man.

And while he doesn’t think this by itself made him the best person to write “How to be Gay,” he conceded that “it perhaps makes me curious in a way that other people are not.”

Jenn McKee is the entertainment digital journalist for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at jennmckee@annarbor.com or 734-623-2546, and follow her on Twitter @jennmckee.