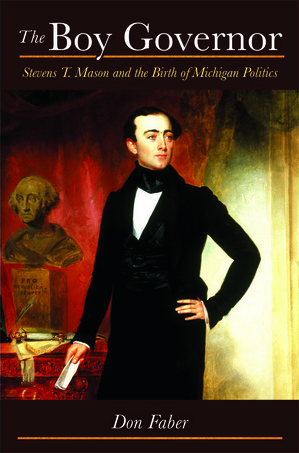

courtesy of the University of Michigan Press

Without Mason, said Faber, Michigan might be missing its Upper Peninsula, the Soo Locks might never have been built, and the University of Michigan might not occupy a fair-sized chunk of Ann Arbor.

“He’s such a pivotal figure in early Michigan history,” Faber said.

In 1831, Mason was named Secretary of the Michigan Territory at the age of 19, two years before he could even vote and the youngest presidential appointee in American history. After championing the territory’s successful push for statehood without congressional authorization, he would defend his new state’s border in defiance of the country’s political elite and then orchestrate its expansion—all before his official election as Michigan’s first governor at age 24, the youngest chief executive in any state’s history.

“He set in place so many institutions that we have today," Faber said. "In one remarkable year he led the fight for statehood, prosecuted that war with Ohio (that resulted in Michigan getting much of the Upper Peninsula in exchange for the so-called Toledo Strip), helped to write the first constitution—a very progressive and liberal document for that time—banned slavery, called for the first superintendent of public instruction, and also managed to get himself fired for insubordination by President Jackson (for his actions) in the Toledo affair. Then, one month later, at the age of 24, he got himself elected the first governor of Michigan”

The Mason biography came out late last year, published by the University of Michigan Press, to roughly coincide with Mason’s 200th birthday. He died from pneumonia at age 31 in 1843, however he lived long enough to see the U-M relocated from Detroit to Ann Arbor and he was on the board of regents ex-officio, Faber said. Mason Hall on the U-M campus is named after him, as is the city of Mason, Mich.

A former editor and columnist for The Ann Arbor News, Faber’s previous book with the University of Michigan Press, “The Toledo War,” was named a Notable New Book by the Michigan Library Association in 2009 and was also named first-prize winner in history writing by the Michigan Historical Society.

Faber said Mason never liked being referred to as the boy governor.

“It was a term that was fixed on him at the time, and it was a term he really disliked. But he had to learn to live with it. In fact it was the editor of one of the two Ann Arbor papers at the time who stuck that term on him. He disliked it so much, so the story goes, that he met (the editor) on the streets of Detroit once, and punched him out.”

Faber said it’s not that much of a stretch to think of Mason as the father of the University of Michigan. “It was Mason who all along, in his governorship, was calling for a state university that would be the ‘ornament and honor of the west,” he said. “This would be an institution that would be ‘unparalleled in the land.’

Oddly enough, Faber even had some alone time with the boy governor, or at least his remains, when the body was exhumed in 2010 so the city of Detroit could revamp the downtown Capitol Park, where Mason is buried.

“I asked permission from the funeral home (I asked) could I come and see the boy governor. I’m a historian, a scholar, not some ghoul, and they said ‘sure come on down.’” Faber recalled.

“I had some time with the open casket - there was a fully intact skeleton and a molar. To me, that was very meaningful, to have a glimpse into history. I only had 10-15 minutes but it was enough for me to kind of drift back in time.”

Although Faber said Mason died in disgrace due to the difficult economic situation his program of building roads, canals and railroads caused Michigan during the financial panic of 1837, the passage of time has clearly burnished his image.

“A century later, I think he’s among Michigan’s foremost statesmen and women,” said Faber. “After Lewis Cass, probably it would be Mason. And even though Cass has the place of honor in statuary hall in Congress, Mason has a place of honor all his own in downtown Detroit at Capitol Park.”

Don Faber will talk about Mason and sign copies of the book at 7:30 p.m. Jan. 24 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, as well as on March 14, at 4 p.m., at the William L. Clements Library. Both are on the University of Michigan campus.